Your cart is currently empty!

No. 8 – Tracing the Origins of Contemporary Christian Music

I remember my first encounter with what has been labeled “contemporary Christian music” as being in 1988. Oh, sacred pop in the form of songs like “Morning Has Broken” and “Let There Be Peace on Earth” had been around for a while, and youth groups had latched onto “They’ll Know We are Christians” and “Pass It On”, but as a church musician in a very traditional mainline Presbyterian Church in the Southeast, I had no experience with a movement gaining steam largely in the western United States.

When I began my career as a full-time church musician in 1974, I had had excellent conservatory training and saw music ministry as a secure and predictable occupation that had not changed for generations. That was not true, of course. The church in the 1960s and 70s, as with the society around it, was experiencing the first pangs of historic change. That just hadn’t yet become apparent in the mountains of North Carolina where I was working. Music was only one element dividing worshippers. The old contentions about Biblical inerrancy versus textual historicism would gradually combine with fractious issues like the ordination of women and gays, abortion, and same sex marriage would pit liberals versus conservatives, traditional versus contemporary, young versus old. The resulting polarization would be of record proportions. As for the origin of Contemporary Christian Music (CCM), numerous writers have dated it either to the Jesus People of the 1960s or the 1965 founding of Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa, both in Southern California. I find neither of these explanations very satisfying. The trend toward Contemporary Christian Music represented a melding of sacred and secular pop music styles which ran counter to most mainline and evangelical thought on church music at the time. Such a radical flip-flop likely could not have sprung forth out of thin air, and this one didn’t.

To really grasp how contemporary Christian music came to be rooted in American Protestant worship, one must first examine the history-making revivals of the post-Civil War decades and their music. Second, one must consider the rise of Pentecostalism in the United States in both the White and African-American church with its strong emphasis on spirit-led worship and often improvisatory singing. Finally, the gradual melding of sacred and secular music in broadcast and recorded media which occurred from the 1920s forward must be taken into account. Each of these milestones are discussed in depth in my book, Servanthood of Song, but here can only briefly be touched upon.

Prior to the Civil War, the United States had been largely rural. The war changed that. In the North, outfitting and arming the Union Army and building railroads to transport it and supplies resulted in an industrial monolith centered in major population centers. Thousands of veterans and their families, as wells as immigrants and southern blacks no longer in bondage, immigrated to cities like New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia. There, often for the first time, they would experience working on an hourly basis in a factory. Clear divisions of caste and class were present in industrial centers, Each had its black community, numerous blue collar and immigrant neighborhoods, and its centers of wealth and prestige usually set back from the city center with imposing gothic temples for worship. While there was some effort focused on fair labor practices and mission efforts in the inner city, the rigid class distinctions remained.

Attitudes regarding sacred music reflected this. Veterans, returning from the battlefields of the Civil War, had found music to be an important anchor of hope during years of sacrifice, violence, and bloodshed. Group singing of familiar songs and hymns – on the march, in regimental worship, and around the campfire – had been a bonding experience for many. The formal worship of elite churches with their organs and paid quartets held little attraction for them. What did inspire these young men and their families was the music of the Great Urban Revival, led at first by Dwight L. Moody and his inestimable songleader, Ira Sankey, and the host of revivalists following them. Familiar hymns including the much-loved Sunday School songs of W. B. Bradbury were mixed with newly-composed evangelistic songs. The gospel hymns of Fanny Crosby would become a staple of these revivals. Less familiar selections were often introduced by a soloist with revival attendees joining in on the easily learned refrains. Often a third of the entire evening was devoted to robust group singing with thousands participating. Predictably, mainline clergy tended to tolerate the revivals as necessary but kept their distance. Despite the growing popularity of the new “gospel songs”, they were roundly condemned by establishment clergy as unmusical doggerel. This point of contention over a matter simply of musical taste in populist versus traditional worship practice would only strengthen and expand in future generations.

The birth of American Pentecostalism, usually dated to the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 Los Angeles, adds another dimension. Pentecostalism’s founders sought to recapture the energy and spirituality of the Christian church at its birth – the day of Pentecost. Worship tended to be “spirit-led” rather than tied to a pre-ordained liturgy and encouraged freedom of expression among worshippers both in testimony and singing. The Pentecostal movement was multi-racial. African Americans moving north to escape Jim Crow in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century often found worship stultifying in the old-line Black churches like Quinn Chapel in Chicago. Instead, they gravitated to newly established “storefront churches”, frequently Pentecostal in worship practice. There, they could sing their own improvised renditions of popular white revival tunes as well as new black gospel entries by Thomas A. Dorsey and others. Meanwhile to the south, the James Vaughan and Stamps-Baxter publishing companies made fortunes selling inexpensive songbooks of new and traditional gospel tunes intended for White Pentecostal worship. The new music was soon building an audience beyond the church as both White and African-American performing artists and quartets found their way into both broadcast and recorded media. One can see this trajectory from worship singer to media celebrity on the African-American side in the careers of Mahalia Jackson, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Aretha Franklin, and Sam Cooke. White quartets like The Blackwood Brothers followed the same trajectory.

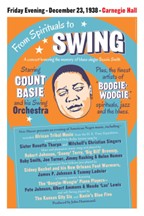

The importance of media influence cannot be overstated. At the time of the American Civil War, most music making for the majority of Americans was a do-it-yourself enterprise. Singing or playing an instrument was a coveted form private entertainment and a creative outlet. One’s church and religious preference set guidelines for what was appropriately to be considered “sacred”. Clear lines not to be crossed were drawn between the music of the church, the opera house, the concert hall, and the saloon. With the advent of railroads, opportunities to experience music performed by touring artists greatly increased. Many White audiences in the North, for example, were first exposed to the African-American spiritual by the touring Fisk Jubilee Singers. In concert, the Jubilee’s travels were largely by rail. Many formerly enslaved Blacks viewed the songs as sacred devotional expressions and questioned the propriety of using them outside of worship. This same ambivalence reared its head when Sister Rosetta Tharpe performed the Thomas A. Dorsey song, “Rock Me”, in a 1938 concert at Carnegie Hall called, “From Spirituals to Swing” which was broadcast nationally Dorsey himself groused that Tharpe’s use of the song was “a desecration”. The dissemination of sacred music through secular media, of course, has continued unabated – from disc recordings, to cassettes, to CD’s, to internet streaming – each further blurring the demarcations between sacred art and secular entertainment.

What we refer to as CCM was born amid this complex web. The Latter Rain Pentecostal preacher, theologian, and revivalist, Reg Layzell (bn. 1904), accepted a call to Abbottsford, British Columbia, in 1946 where he birthed a powerful philosophy of worship based on Psalm 22:3, “But thou art holy, O thou that inhabitest the praises of Israel”(KJV), and Hebrews 13:15, “By him therefore let us offer the sacrifice of praise to God continually, that is, the fruit of our lips giving thanks to his name” (KJV). A fundamental component of Layzell’s theology was that sung praise was the ultimate declaration of love for God. Initially, Latter Rain music was completely improvisatory. There were no songbooks and the melodies, unaccompanied with some sung in harmony, were credited to the movement of the Spirit. This changed in 1949 with the publication of Phyllis Spiers’ Spiritual Songs by the Spiers, and in 1952 with Scripture Set to Music by Rita Kelligan. Songs in Kelligan’s collection, short musical settings of texts taken verbatim from Scripture. The music and worship of the Latter Rain movement included several characteristics which would be embraced and amplified by the contemporary Christian movement two decades later. These included:

- A period of continual praise through singing lasting up to an hour which was an essential component of worship for Layzell and his followers .

- The concept of “Flow”: The singing was intended to move from exuberant praise to a period of heartfelt adoration in God’s presence. To achieve this, techniques were gradually developed to move seamlessly from song to song and theme to theme, through tempo changes and key relationships.

- Songs tended to be short, repetitive, and easily taught. Accompaniments were intended to be improvisatory with piano and guitar being favored.

And so we arrive at the 1960s. As we have seen, the musical precedent was already in place for the rise of Contemporary Christian Music but additional factors came into play. Certainly, the burgeoning folk music revival of the late 1950s and 1960s with its prominent use of guitars played a role. So also was the “Jesus Movement”. A reporter interviewing the activist Episcopal priest, Malcolm Boyd (1923 – 2015), asked for his observations regarding the amorphous gathering of faith seekers:

The underground church he described is not formally organized, has no bishop or anything comparable, and no rites or membership laws… He said members of the underground church include people ‘in no church’, Catholics, and Protestants who have ceased to be active in their own church life. And Catholics and Protestants who have no intention of leaving their churches but deplore their inertia. They seek to renew it, to revitalize it.

The movement Boyd was describing would become known as the “Jesus People”, a term which first appeared in the writings of Duane Pederson in The Hollywood Free Press. A watershed moment in the rise of CCM was the founding in Southern California in 1965 of a small, independent, very traditional Pentecostal church, Calvary Chapel. It was located near the popular beach communities of Huntington Beach, Newport Beach, and Venice. A catalyst for bringing all these factors together was the notorious “Summer of Love” in 1967. Pianist and guitarist Tom Stipe recalled that area beaches were populated by “swarms of culturally orphaned young people looking for love, peace, sex, drugs and rock n’ roll. They were called by many . . . A recipe for revival existed for every side of the spiritual spectrum in that assortment of youthful humanity.”

Calvary Chapel’s pastor, Charles Ward (“Chuck”) Smith (1927 – 2013), saw potential for ministry in the youthful influx and preached a message that appealed to the disaffected teenagers and young adults: the end times and the coming of the Apocalypse. He pioneered a less formal, contemporary approach to worship including services on the beach and baptisms in the Pacific Ocean. The music of the Jesus People, at least initially, was simple, folk-influenced, and ideally suited to informal group singing and evangelistic witness in the out-of-doors. Some songs, now well-known even in non-Pentecostal circles, became theme songs for the movement. One of them was “They’ll Know We are Christians by Our Love”. Such songs were relatively short, often with a traditional verse/chorus format. The repeating choruses were easily memorized even for those new to the group. The guitar accompaniments were built entirely on primary chords and could easily be strummed by inexperienced players. Songs with this simple verse/chorus format quite naturally became a key part of Calvary Chapel worship and Bible studies which usually included an extended period of informal group singing. Fortunately, a virtual template for both songs and worship approach had been developed over a decade earlier by Reg Lazell and his followers.

It was not unusual for traditional, conservatory-trained church musicians like myself to see the onslaught of CCM as being on the losing side of a sort of Armageddon. Even today, if one focuses only on the current situation and statistics, that gloomy perspective is understandable. But it should not be that way. Viewed through the lens of history, we can see that the recent worship wars pitting traditional, classically-oriented worship music versus contemporary praise are but the latest example of divisions regarding music in worship. We must see the current turmoil not as a duel to the death but a reminder: History shows that, in most every case, where ministry – not musical style – is made the priority much dissension can be avoided.

Best wishes and Peace,

Stan McDaniel

[8] Tom Stipe, “The Calvary Chapel Chronicles: The Music.” The Phoenix Preacher (Blog. https://phoenixpreacher.com/the-calvary-chapel-chronicles-the-music-by-tom-stipe/)

AUTHOR

Stan McDaniel

©2023 Stanley R. McDaniel, All Rights Reserved.

Copying or re-publication is expressly prohibited without direct permission of the author.

Leave a Reply